In the early 1900s, Marie Curie discovered radium, and it became an instant phenomenon. It was used as a treatment for cancer, baldness, and believed to make women more beautiful. The full of effects of radium were not yet clear. Madam Curie died of complications from anemia, caused by prolonged exposure to radium. But by the time she died in 1934, other women were dying from radium as well.

In 1917, a new trend emerged in the form of “glowing” watches. These watches had the numbers painted with glow-in-the-dark radium paint. This was painstaking work, and 4,000 employees, most of them women, were hired to paint the numbers on the faces for 1.5 cents per watch. While scientists were beginning to understand the effects of radium on the body, the women working in watch factories—who would become known as Radium Girls—still believed it to be a miracle cure-all.

The women were taught to paint the watch faces using a method called “lip pointing,” where they put the tip of their paintbrushes between their lips to sharpen the point. Repeated lip pointing led to lips and teeth coated in paint and radium seeping into their bodies. Many women, however, did not stop at lip pointing. Believing that the radium would make them healthier, they painted the glow-in-the-dark paint on their lips, teeth, eyelids, fingernails, and buttons. The radium then soaked into their bloodstreams, poisoning them.

Very quickly the Radium Girls started developing health problems. Their teeth began to rot because of the exposure from lip pointing. When the rotten teeth were removed, their jaws broke as well, weakened and brittle. The extraction sites did not heal but became infected, causing further health concerns. Other women developed bone cancer, anemia, and leukemia from exposure.

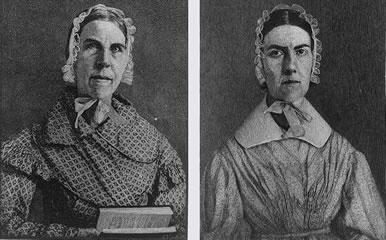

By 1927—within ten years of the radium watches being produced—more than fifty women died as a direct result of radium poisoning. In 1927, after contracting cancer, Grace Fryer, one of the Radium Girls, led a group of women in suing the factory owner of U.S. Radium Company. Their victory set a precedent for workers having rights in cases of occupation-related diseases. Eleven years later, Catherine Donahue also sued, taking the company she worked for to court. She was so sick by the time the trial was held that she had to be carried into the courtroom to testify. Donahue also won her case but died shortly after.

The Radium Girls are an example of exploitative labor and the power to fight it. Hundreds of these women died from radium related diseases over the years, and even after scientists decided radium was unsafe to ingest, factory owners continued to make the women paint the watch faces. These women died, but their legacy led to tighter regulations on worker safety and rights of the worker.

Works Cited

Grady, Denise. “A Glow in the Dark, and a Lesson in Scientific Peril.” The New York Times. Published 6 October 1998. Accessed 20 February 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/06/science/a-glow-in-the-dark-and-a-lesson-in-scientific-peril.html?pagewanted=all.

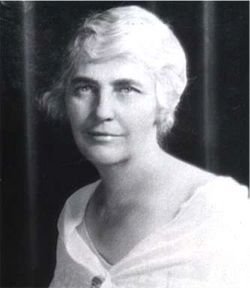

Hersher, Rebecca. “Mae Keane, One of the Last ‘Radium Girls,’ Dies at 107.” NPR. Published 28 December 2014. Accessed 20 February 2016. http://www.npr.org/2014/12/28/373510029/saved-by-a-bad-taste-one-of-the-last-radium-girls-dies-at-107.

Schlender, Shelley. “Watch’s Deadly Glow Recalls Worker Tragedy, Triumph.” Voice of America. Published 3 January 2011. Accessed 20 February 2016. http://www.voanews.com/content/watchs-deadly-glow-recalls-worker-tragedy-112885149/169008.html.